|

|

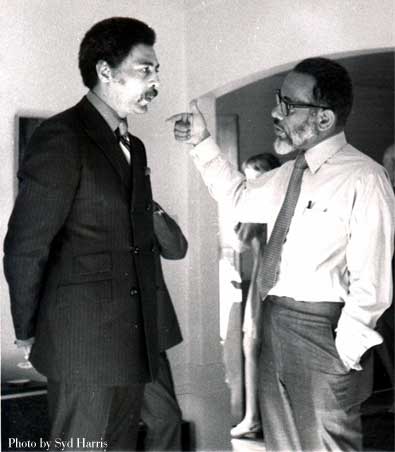

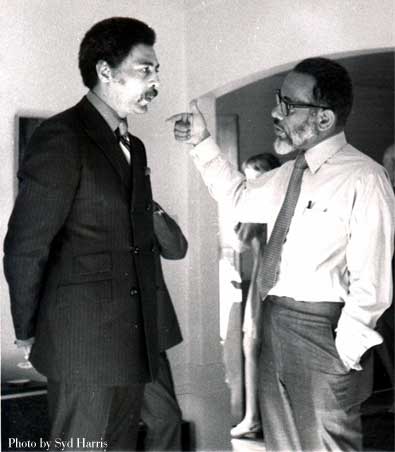

C.B. King with

|

C.B.King was one of the country's most prominent and courageous civil rights lawyers. For over 30 years, C.B. practiced law in Albany, Georgia, where he was a major figure in the civil rights movement. He was a tireless and enormously talented lawyer. He earned the respect and admiration of the many people in the civil rights movement who depended on his advice, counsel and friendship.

He was also a great teacher. In his office, on the streets and in the courtroom, C.B. King taught several generations of law students and young lawyers how to practice law with a commitment to the poor, the disenfranchised and the oppressed. Each summer in the 1960s and early '70s, these students and lawyers worked with C.B. on the numerous cases generated by the civil rights struggle. For many of us, that experience was a decisive turning point in our lives. Working with him was an unqualified privilege: we had the opportunity to learn from a skilled advocate for racial justice.

The following excerpt is by C.B. King from The Peoples Lawyers by Marlise James.

I came to Albany and started my practice on South Jackson street in the back of a funeral home in 1954. I fixed the space to which I was assigned t look like a law office, but the funeral home was fittingly symbolic of the putrescent state of the law hereabouts. During those days I was the only Black lawyer southeast of Atlanta.

Leading up to the time of one of my early trials, I had my first encounter with a local sheriff, who later bludgeoned me. Very early upon my return to Albany, one of his deputies, who is the present sheriff of this county, attempted to assign me a certain seat in the courtroom. This particular courtroom accommodated two jury boxes, one on the right (the one regularly used by the trial jury) and another one on the left of the judge's bench. It was a practice of lawyers to use the auxiliary jury box. So as I proceeded to wittingly exercise what had heretofore been the exclusive right and privilege of white lawyers, to sit and observe the law at work from close up, those that were in proximity to the seat I selected took flight to the far reaches of the courtroom in horror. The second day I again sat there and upon this occasion the sheriff came over and told me, 'Go sit with them other niggers.' I was numbed by my embarrassment and by the surrealism of pretended oblivion and snickering of lawyers and other court officers which, to my mind reasserted my almost forgotten identity. This encounter abrasively reasserted an identity I was in the process of forgetting. I explained to the sheriff that, as an officer of the court, I had a right to use the jury box as did the others.

At this time it was close to the time of the trial of my client, the boy who had been charged with resisting arrest whom I was yet to defend. I left my seat attempting to convince myself that in so leaving I was not yielding to the sheriff's threats but rather recognizing my duty and concern not to prejudice the case against my client. I walked out into the rotunda with the sheriff and protested this patent differential treatment. The sheriff said, "We ain't had no trouble before you come here, we ain't going to have none now." I walked to the outside of the courthouse in an effort to overcome a sort of drowning that is common to humans who have been stripped of a sense of self. Yes, I cried a bit as well. I justified my leaving, on command of the sheriff, upon concern for my yet untried criminal client.

Following the trial I was brought face to face with my pledge to prevail as the equal of any man by sitting among and pitting my skills against my white antagonist, or, alternatively, facing the forced acknowledgment that I had indulged in self-deception by leaving the courtroom and addressing as the cause therefor the concern for my client, instead of the traditional Black fear of white authority. So the next day I returned to the courtroom and to the jury box from whence I had previously gone, somewhat unsure in my own mind as to whether my previous leaving was really responsive to my concern or submission to fear. Again the sheriff came and said, "Goddamn it nigger, I thought I told you to get back there with them other niggers. Do you want me to hurt you?" I looked into the face of the sheriff as dispassionately and as calmly as I could under the circumstances and said, "Sheriff, that's what you will have to do, I'm staying here." He then told me that he'd give me five minutes to move back to the area in the courtroom the which Blacks were relegated. The sheriff did in fact return some fifteen minutes later. The interim between the sheriff's last warning and his return to the courtroom represented moments of intractable nightmarish anxiety for me. I expected at any moment that he would return and there brutalize me in this forum of white justice. When he did return, instead of coming to where I was, he went to the judge's bench and in that instance I was sure that I had prevailed. Apparently the judge did not encourage the sheriff to forcibly remove me from my seat.

Six years later I was trying to get into the county fail to see a white SNCC client of mine who had been beaten by some white thugs who were cellmates of his. This sheriff, by whom I had previously been verbally abused, came into his outer office and interrupted a conversation I was then engaged in with one of his deputies. He told me to get out of his office and wait in the hall. He left, and in a moment came back and said, "You goddamn Black sonofabitch, you still here?" Whereupon he struck me on the forehead with a walking cane, which broke under the force of his blow. He used the remnant of the cane to strike me on the back of my neck as I ran, bleeding, into the hallway.

Over the years that I've practiced in south Georgia, I have had many similar experiences (absent physical violence) with sheriffs all over rural Georgia. In the early civil rights struggle, an Early County, Georgia, sheriff had a client of mine from Bayonne, New Jersey, in jail. He had been arrested, arraigned, plea of guilty accepted to murder and rape charges, and sentenced to die in the electric chair, all within forty-eight hours. When visiting my client, I inquired casually of the sheriff whether he was sure he had the right man. His response was, "Damn right." The more I went to the jail to see the man, the more certain of my client's guilt the sheriff became. Subsequently, I obtained a federal writ of habeas corpus and went to the jail with it, and, as he read audibly the content of the writ, he was heard to say, "I've been good to you niggers, trying to treat you like a lawyer, C.B. There is limits beyond which patience ain't no goddamn virtue. Now get out of here." Despite him I was finally successful in obtaining a reversal of the sentence and the charges were ultimately dropped against my client.

Virtually every aspect of the law, as it relates to my practice, concerns the civil rights and civil liberties of those whose causes I represent. Tragically, my seventeen years of practice make me know that the overriding reality of the Black experience in this country is the forced relevancy of race. I now recognize that branches of government-federal, state, and other inferior political subdivisions as well-deliberately promulgate the organic law, administer its benefit, and most generally interpret its meaning in a way most beneficial to those persons or classes that have the least melanin. Despite this the law has been a kind of therapy for me. I served to quell, to some reasonable extent, feelings of aggression I had acquired in growing into manhood in the South. To that extent the law has been kind to me psychologically. I have a couch in my office which is little use. Hopefully, the law will continue to be therapeutic. Should it fail I shall then be forced to take refuge in my couch. Hopefully, it will suffice.

I have seen some indication on the part of young whites in high school and college that shows a variance with the attitudes of their forbears. But is this sufficient to stem the tide? I think something has to be done, in a more organized and deliberate way, or the whole thing goes down the drain. Though I am impressed with some of what I see from young white lawyers, I wonder if the attitudes of Paul, Dennis, Stan and the others is still current in law schools today.

Information | Workshops | Articles | Profiles | Contact us | Links | Reviews | Home